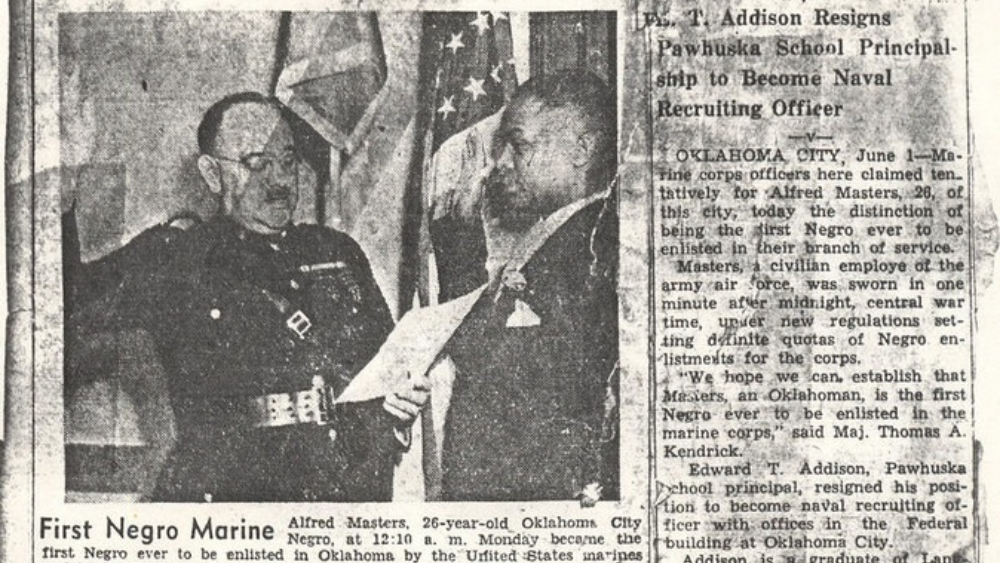

On June 1, 1942, Alfred Masters made history when he became the first Black man to enlist in the United States Marine Corps since the Revolutionary War. His enlistment marked the beginning of a transformative era in the military, breaking long-standing racial barriers in the U.S. armed forces. Though often overlooked in mainstream historical narratives, Masters’ contribution paved the way for thousands of African American Marines who followed in his footsteps.

The Road to Change: Segregation in the U.S. Military

Before World War II, African Americans had been largely excluded from the U.S. Marine Corps. The last time Black men served as Marines was during the American Revolution, when both free and enslaved Black men fought in various capacities. However, after the Revolution, the Marine Corps adopted a policy of racial exclusion that lasted for more than 160 years.

During World War I, African Americans served in segregated units in the Army and Navy, often relegated to support roles rather than combat positions. Despite their willingness to fight and their proven capabilities, Black men were denied entry into the U.S. Marine Corps entirely. This exclusion persisted until the 1940s, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt, under pressure from civil rights activists and the Black press, issued Executive Order 8802 in 1941. This order prohibited racial discrimination in the defense industry and led to the eventual integration of African Americans into all branches of the military, including the Marines.

The First Black Marine Since the Revolution

On June 1, 1942, Alfred Masters enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. His historic enlistment was not just a personal achievement but a symbolic victory in the fight for racial equality. As World War II engulfed the United States and the demand for manpower soared, Masters chose to join the Marine Corps, breaking racial barriers.

Master’s enlistment was part of a broader effort by the U.S. Marine Corps to comply with the executive order and recruit African American men. However, the Marine Corps did not fully accept these men as equals, training them separately from white recruits and sending them to Montford Point, a segregated training facility in North Carolina, instead of the traditional U.S. Marine Corps Recruit Depot at Parris Island or San Diego.

Training at Montford Point

Alfred Masters and his fellow Black recruits faced significant challenges at Montford Point. The training camp, established in 1942, was located near Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. Unlike their white counterparts, Black Marines trained in isolation under the supervision of white officers. Montford Point had harsh conditions—housing lacked adequacy, and Black recruits frequently endured extreme racism inside and outside the base.

Despite these obstacles, the Montford Point Marines excelled in their training, demonstrating the same discipline, skill, and dedication as any other Marine unit. They learned combat tactics, weapons handling, and physical endurance, proving that race had no bearing on military capability.

Breaking Barriers in Combat

Although initially restricted to labor and support roles, Black Marines gradually earned the opportunity to serve in combat. The Montford Point Marines saw action in the Pacific Theater, particularly during key battles such as Iwo Jima, Saipan, and Okinawa. These men transported ammunition, repaired vehicles, and eventually engaged in direct combat.

Alfred Masters’ pioneering enlistment opened doors for more than 19,000 African Americans who trained at Montford Point between 1942 and 1949. Their contributions played a crucial role in the eventual desegregation of the U.S. Marine Corps and the broader U.S. military.

Legacy and Recognition

For many years, the contributions of Alfred Masters and the Montford Point Marines were largely ignored in historical accounts of World War II. However, their legacy was finally acknowledged decades later.

In 2011, the U.S. government awarded the Montford Point Marines the Congressional Gold Medal, one of the highest civilian honors. This recognition honored their courage, perseverance, and the pivotal role they played in integrating the U.S. Marine Corps.

Alfred Masters’ decision to enlist in 1942 was not just a milestone in military history—it was a crucial step in the broader civil rights movement. His bravery and the determination of his fellow Montford Point Marines proved that Black Americans had the right and the ability to serve their country with honor and distinction.

Alfred Masters’ enlistment as the first Black Marine since the Revolutionary War signified more than just a personal achievement. It was a turning point in U.S. military history, challenging decades of racial discrimination and laying the foundation for a more inclusive armed forces. His legacy lives on through the thousands of African American Marines who followed in his footsteps and through the continued fight for equality and recognition in all aspects of American life.