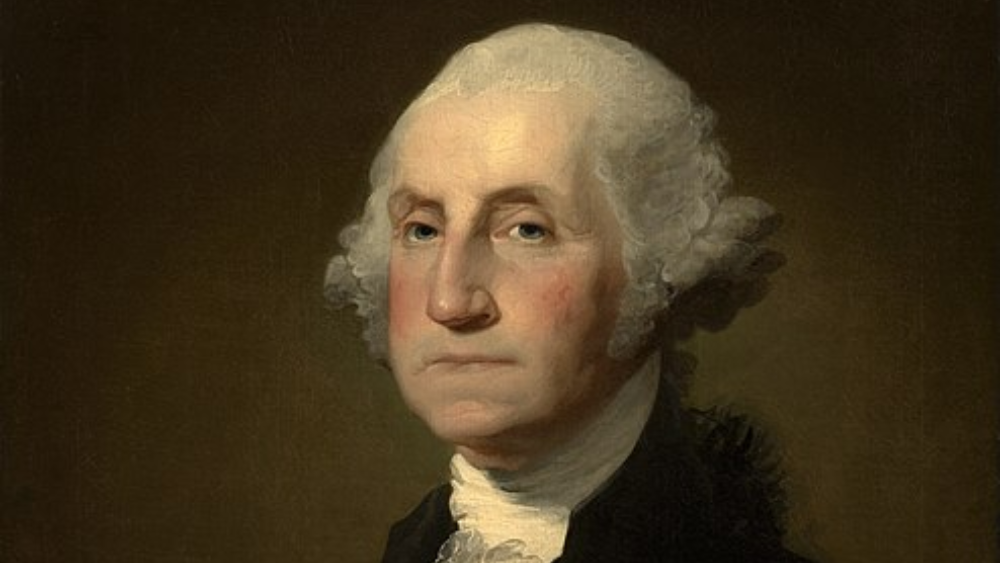

George Washington, an American military commander, politician, and founding father, died on December 14, 1799. He served as the country’s first president from 1789 to 1797 and left behind a legacy that would shape the identity and values of the United States for generations.

The Second Continental Congress appointed Washington as the commander of the Continental Army in June 1775, marking the beginning of his pivotal role in the fight for American independence. After years of military leadership and public service, he became an enduring symbol of integrity, humility, and dedication to the greater good.

He later presided over the 1787 Constitutional Convention, which drafted and ratified the United States Constitution and established the federal government. This foundational moment of governance has since guided the principles of American democracy.

Due to his extensive contributions to the country’s formation, Washington has earned the moniker “Father of his Country.”

From Surveyor to Revolutionary General

Washington’s first elected position was Surveyor of Culpeper County, Virginia, a post he held from 1749 to 1750 when he was only 17 years old. He demonstrated keen intelligence and discipline, which helped him gain the respect of the Virginia aristocracy. He commanded the Virginia Regiment during the French and Indian War after completing his initial military training, giving him invaluable combat experience and knowledge of frontier warfare.

Later, he was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he began forming political relationships with other influential figures in colonial America. He was then designated a delegate to the Continental Congress, which named him Commanding General of the Continental Army, entrusting him with leading the colonies in their most critical fight for freedom.

Under his leadership, American forces, with help from French allies, defeated the British at the Siege of Yorktown in 1781, effectively ending the Revolutionary War. After the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, which recognized American independence, Washington resigned from his commission, a gesture that cemented his reputation as a leader who valued democratic principles over personal power.

From 1759 until the start of the American Revolution, Washington ran his plantations near Mount Vernon while also serving in the Virginia House of Burgesses. During this time, he honed his leadership skills in both agriculture and politics.

He married Martha Dandridge Custis, a wealthy widow with two children, in 1759. Their union brought both personal contentment and financial stability. However, like many landowners of his time, Washington grew increasingly frustrated with British policies. He believed British merchants were exploiting American planters and viewed British laws as overly restrictive. Though his protests were initially measured and diplomatic, they became more pointed as the colonial crisis deepened.

George Washington on Social Norms and Education

Washington attended the Lower Church School in Hartfield, but unlike his older brothers, he did not receive a formal education in England. Despite this, he became a self-taught scholar. He was a skilled draftsman, mapmaker, and land surveyor, and he studied arithmetic, trigonometry, and geography—subjects essential to managing large estates and commanding military units.

As a teenager, Washington meticulously copied and memorized the “Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation,” a list of 110 social maxims derived from a French text. These rules taught values such as respect, humility, and discipline—virtues that would guide him throughout his life. This early moral framework laid the foundation for Washington’s sense of personal responsibility and public duty.

Washington also had a deep appreciation for education and believed it was essential for maintaining liberty. He once wrote, “Promote then, as an object of primary importance, institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge.” While he never founded a university himself, he left provisions in his will to support the establishment of a national university in the capital.

Civil War Military Service and Colonial Conflicts

Washington’s first military involvement came through his brother Lawrence Washington, who served as the adjutant general of Virginia’s militia. When Lawrence died in 1752, George inherited the family estate and pursued a military career in his brother’s footsteps.

Lieutenant Governor Robert Dinwiddie appointed Washington a major and assigned him to defend the British interests in the Ohio Valley, a region heavily contested by the British and the French. He led a small force that engaged French troops at Jumonville Glen in 1754, a confrontation that helped spark the French and Indian War.

Though the campaign included both successes and failures, such as his surrender at Fort Necessity, it established Washington’s reputation as a brave and determined leader. He also learned difficult lessons about military logistics, frontier warfare, and the challenges of coordinating colonial militias.

Washington later traveled to Barbados in 1751 with his ailing brother, hoping the tropical climate would improve Lawrence’s health. During this trip—Washington’s only journey abroad—he contracted smallpox, which left lasting facial scars. Tragically, Lawrence passed away the following year, and George eventually inherited Mount Vernon, the now-iconic estate located along the Potomac River.

A Gentleman Farmer and an Officer

Washington increased Mount Vernon’s original 2,000 acres into an 8,000-acre estate with five farms throughout the subsequent years. He raised several crops, including wheat and corn, bred mules, cared for fruit orchards, and operated a prosperous fishery. He was keenly interested in farming and always experimented with new crops and ways to preserve the land.

In December 1752, they appointed Washington, who had no military training, as the head of the Virginia militia. He participated in the French and Indian War before being given command over all of Virginia’s militia units. The Virginia House of Burgesses elected Washington in 1759 after he had resigned his office, retired to Mount Vernon, and remained there until 1774.

He wed Martha Dandridge Custis (1731–1802), a wealthy widow with two kids, in January 1759. Washington and Martha never had children of their own, so he became a devoted stepfather. His private life reflected the same values of stewardship and responsibility that defined his public career.

George Washington and His Journey to Independence

By the late 1760s, Washington had become an outspoken critic of British taxation and trade policies, particularly the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts. His extensive correspondence and public statements reveal his belief that British rule was increasingly exploitative and unjust.

In 1774, Washington served as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia, where he joined others in calling for colonial rights. A year later, the conflict had escalated into full-scale war. When the Second Continental Congress convened in 1775, it appointed Washington as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army due to his leadership skills, military background, and unwavering commitment to the cause.

Though Washington suffered several battlefield defeats—including early losses in New York—his strategic withdrawals kept the army intact. His surprise attack on Trenton in December 1776 and subsequent victory at Princeton, boosted morale and inspired renewed support.

One of Washington’s most trying moments came during the harsh winter at Valley Forge (1777–1778). With supplies running low and morale at its lowest, he managed to hold the army together through sheer determination, charisma, and the help of Baron von Steuben, who trained the troops and instilled much-needed discipline.

Washington’s persistence and coalition-building with France ultimately turned the tide. The Siege of Yorktown in 1781, with French support, resulted in a decisive victory and the eventual end of British rule in the colonies.

Presidency and Legacy

After the war, Washington again shocked the world by voluntarily stepping down from power and retiring to Mount Vernon. This act of selflessness earned him global admiration and reinforced his commitment to republican values.

But in 1787, he returned to public service to preside over the Constitutional Convention, where his leadership helped ensure the success of the U.S. Constitution. His steady, impartial presence provided a model for the office of the presidency itself.

Elected unanimously as the first President of the United States in 1789, Washington set countless precedents, including forming a Cabinet and serving only two terms. He navigated internal strife, foreign threats, and partisan division while promoting unity and national identity.

He supported policies that strengthened the federal government, launched a national bank, and promoted infrastructure. At the same time, he stressed neutrality in foreign affairs, especially in his 1793 Proclamation of Neutrality during the war between France and Britain.

His Farewell Address in 1796 warned against political parties and foreign entanglements—advice that remains remarkably relevant today. In it, he wrote, “The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge… is itself a frightful despotism.” These words still resonate in today’s divided political climate.

When he died in 1799, the entire nation mourned the passing of a leader whose vision, integrity, and humility helped shape the United States of America. Henry Lee, a fellow Virginian, influentially described Washington as: “First in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen.”

Conclusion

George Washington was more than a military commander or a political figure; he was a symbol of the ideals that define the American spirit. From a young surveyor on the Virginia frontier to the first president of a new nation, his life was a testament to resilience, leadership, and an unshakeable belief in the principles of liberty and democracy.

His ability to lead in times of uncertainty, his refusal to seize power for personal gain, and his commitment to shaping a republic grounded in civic responsibility continue to inspire people around the world.

Today, Washington’s legacy lives on—not just in monuments or currency, but in the very framework of the nation he helped build. His life is a guiding light for leadership based on principle, humility, and service to others. And for every generation of Americans, he remains the founding father who defined what it means to lead not just with power—but with purpose.