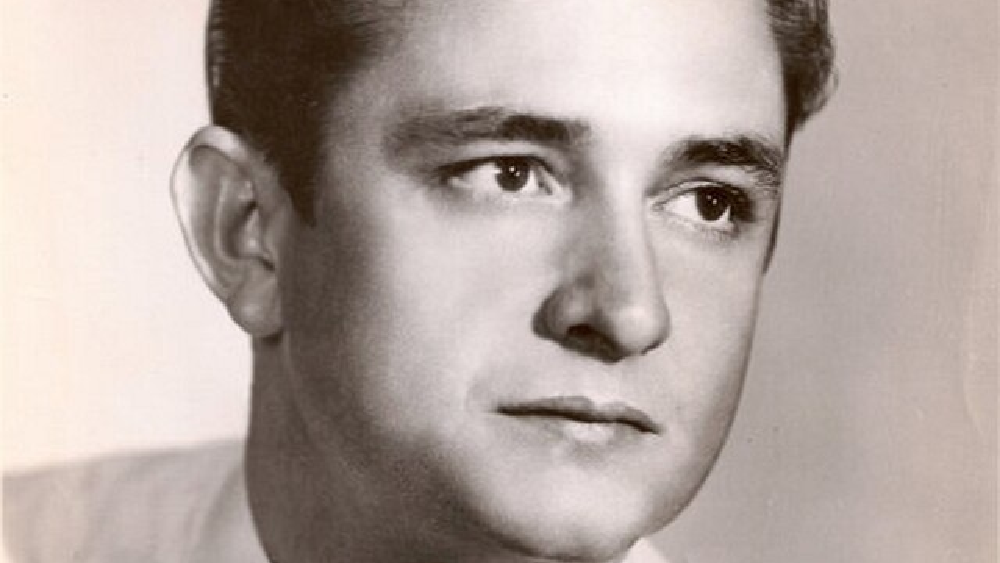

Johnny Cash was never just a musician. He was a witness of: pain, faith, failure, and redemption. Born J. R. Cash on February 26, 1932, in Kingsland, Arkansas, he grew into one of the most recognizable and influential voices in American music history. When Johnny Cash sang, he didn’t perform for people—he stood with them: prisoners, the less fortunate, the forgotten, and the faithful who struggled daily with doubt.

Born of Cotton Fields, Hymns, and Hunger

From the very beginning, Cash’s life was shaped by hardship. Raised by poor cotton farmers during the Great Depression, he learned early what it meant to work, to suffer, and to endure. As a child in Dyess, Arkansas, he labored in the cotton fields alongside his family, singing gospel hymns as the sun beat down. Those songs—rooted in faith, sorrow, and hope—never left him. They became the emotional backbone of his music.

Johnny Cash did not walk into the U.S. Air Force dreaming of becoming “The Man in Black.” He walked in because in 1950 a poor kid from Arkansas had limited options, and the Korean War draft was knocking on doors like an impatient sergeant. What came out of that decision shaped not only his music, but the way generations of veterans would later recognize themselves in his voice.

Johnny Cash’s Military Service in the U.S. Air Force

Cash enlisted in the Air Force in July 1950, straight out of high school, and was sent to Lackland and then Keesler Air Force Base for training. Eventually he landed in Landsberg, Germany, assigned to the 12th Radio Squadron Mobile as a Morse code interceptor.

That job sounds clean on paper. In reality, it meant long shifts wearing headphones, copying Soviet communications letter by letter, sitting in silence while the Cold War hummed quietly in the background. No firefights, no medals for valor—just the kind of pressure that comes from knowing the wrong mistake could ripple far beyond your desk.

For veterans, that part hits home. Not every war story has explosions. Some are built from boredom, tension, isolation, and responsibility that never really shuts off.

Landsberg, Isolation, and the Weight of History

Landsberg carried its own weight. The base sat near the ruins of the Nazi prison where Hitler had once been held after the Beer Hall Putsch. Cash later said the place felt haunted. Young airmen stationed there were surrounded by reminders of what unchecked power and war could do.

Nights were cold. Letters from home took forever. Alcohol was cheap. Loneliness was expensive.

It was in that environment that Johnny Cash started to become Johnny Cash.

Music, Discipline, and the Birth of a Voice

He bought a cheap guitar and began writing songs in the barracks. The Air Force gave him discipline and routine, but music gave him oxygen. One night, after hearing news of Stalin’s death over the radio, he wrote a song that would later become “Folsom Prison Blues.”

The line “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die” wasn’t autobiography. It was empathy. Cash was already tuning his ear toward the forgotten, the locked-away, the men on the margins. Veterans recognize that instinct. Military life teaches you quickly who gets remembered and who gets buried in footnotes.

Cash was honorably discharged in 1954 as a staff sergeant. No scandals, no glory. Just four years of service, a duffel bag, and a head full of songs.

Why Johnny Cash Still Resonates With Veterans

What came after is what most people know. Sun Records. But veterans hear something different in his music.

They hear a man who understood systems, orders, confinement, and consequences. “I Walk the Line” sounds like a love song, but it also sounds like a young serviceman promising himself not to screw up his life. “San Quentin” and “Folsom Prison Blues” feel less like performances and more like after-action reports from a man who never forgot what authority can do to a human being.

Cash never claimed to be a war hero. He rarely talked about medals or missions. He talked about people—enlisted men, prisoners, Native Americans, working-class families—the ones history usually files under “miscellaneous.”

That is why his connection with veterans runs deeper than nostalgia.

Johnny Cash understood duty without romanticizing it. He understood rules without worshiping them. He respected the uniform, but he always kept his loyalty with the people inside it. When he sang for prisoners, hospital patients, or wounded veterans, it never felt like charity. It felt like kinship.

For today’s veterans, his story carries a quiet message: military service does not have to define your rank forever, but it will shape your voice whether you like it or not. Discipline can turn into art. Loneliness can turn into empathy. Four years in a cold listening post in Germany can echo across a lifetime.

Johnny Cash left the Air Force before he became famous—but the Air Force never really left Johnny Cash.

The Brother He Never Stopped Mourning

One tragedy, however, haunted him for life. In 1944, Cash’s beloved older brother Jack died after a horrific accident involving a table saw. Johnny carried guilt from that loss into adulthood, believing he should have been there instead. That sense of sorrow and his constant awareness of mortality would later echo through songs filled with grief, reflection, and longing for grace.

Sun Records and the Sound of Reckoning

That determination led him to Memphis and Sun Records, where he found himself among future legends like Elvis Presley, Carl Perkins, and Jerry Lee Lewis. Cash’s early sound—defined by his deep bass-baritone voice and the unmistakable “train-chugging” rhythm of his band, the Tennessee Three—stood apart. Songs like “Cry! Cry! Cry!”, “Hey Porter”, and especially “Folsom Prison Blues” announced the arrival of an artist who sang about crime, consequences, and conscience with startling honesty.

Cash famously opened many of his concerts with the words, “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash,” before launching into “Folsom Prison Blues.” It was more than an introduction—it was a declaration. He wasn’t pretending to be an outlaw. He was giving voice to the men who were.

Success, Self-Destruction, and the Weight of Black

Despite his growing success, Cash’s life offstage was unraveling. Fame amplified his struggles with alcohol and prescription drugs, and by the early 1960s, addiction had taken hold. His behavior grew erratic, his marriage to Vivian Liberto collapsed, and his reputation became as dark as the black clothes he wore. Yet even during his lowest moments, his creativity burned fiercely. Songs like “Ring of Fire,” “I Walk the Line,” and “Man in Black” captured the tension between desire and discipline, rebellion and belief.

Black as Mourning, Protest, and Promise

The color black became his symbol. Cash said he wore it for the less fortunate, the prisoner, the sick, and those society chose not to see. It wasn’t fashion, instead it was protest, mourning, and solidarity.

Singing Where Hope Was Caged

One of the most defining acts of his career came through his prison concerts. Beginning in the late 1950s and immortalized by At Folsom Prison (1968) and At San Quentin (1969), Cash brought dignity and humanity to incarcerated men. These performances weren’t gimmicks. Cash understood prison life emotionally, if not literally. Though he was arrested several times, he never served a prison sentence—but he knew what it meant to feel trapped by one’s own choices.

Songs That Refused to Look Away

Alongside his advocacy for prisoners, Cash became a vocal supporter of Native American rights, releasing Bitter Tears in 1964—an album that openly confronted the violent oppression of Indigenous peoples. The record faced resistance from radio stations and industry leaders, but Cash refused to back down. He used his fame not for comfort, but for confrontation.

The Woman Who Helped Him Stand

Redemption, however, arrived through love and faith. June Carter, whom Cash had admired for years, stood by him during his darkest battles. After years of addiction, arrests, and near collapse, Cash proposed to June onstage in 1968. Their marriage became the anchor of his recovery. With June’s help—and a renewed commitment to his Christian faith—Cash slowly reclaimed his life.

Belief Without Illusion

Still, the road was never smooth. Relapses followed, as did rehabilitation. Cash never portrayed himself as healed or holy. He called himself “the biggest sinner of them all.” That honesty made his faith credible. It was lived, not preached.

Johnny Cash: When the World Heard Him Again

In the late 1990s, when many thought his career was over, Cash experienced an extraordinary resurgence. Partnering with producer Rick Rubin, he stripped his music down to its bare bones. The American Recordings series presented an aging Cash—frail, reflective, and fearless. His cover of Nine Inch Nails’ “Hurt” became a haunting farewell, transforming a song about self-destruction into a meditation on regret, memory, and grace.

A Farewell Etched in Silence and Memory

The video, showing Cash surrounded by relics of his past, is widely considered one of the most powerful music videos ever made. Even Trent Reznor, the song’s original writer, admitted that it no longer felt like his song—it belonged to Johnny Cash.

After June Carter Cash died in May 2003, Johnny was heartbroken but determined to keep working. Music, he said, was the only thing keeping him alive. He died just four months later, on September 12, 2003, at the age of 71.

What Remains After the Last Note

Johnny Cash left behind more than hit songs and awards. He left a legacy of truth-telling, singing about sin without glamorizing it, about faith without denying doubt, and about America without pretending it was perfect. He stood at the crossroads of country, rock, gospel, folk, and blues—belonging fully to none, yet essential to all.

In the end, Johnny Cash wasn’t remembered because he was flawless. He was remembered because he was real. A man in black, carrying light.