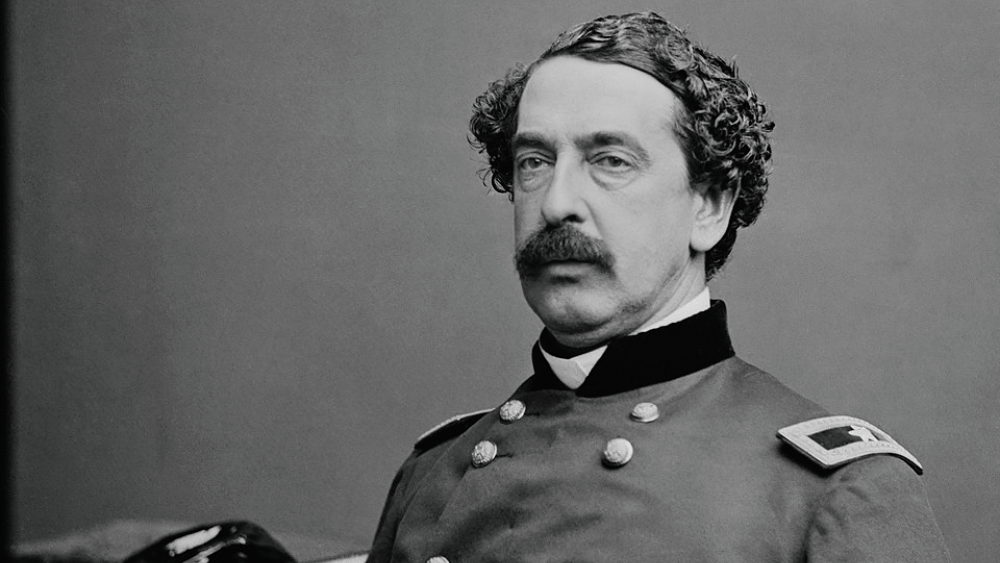

Growing Up and Finding His Way

Born on June 26, 1819, in Ballston Spa, New York, Abner wasn’t exactly raised in the sticks. His dad, Ulysses, was a congressman, so the house buzzed with talk of politics and duty. Young Abner had a head for numbers and puzzles, which nudged him toward West Point. He graduated in 1842, rubbing shoulders with future big shots like James Longstreet. No fireworks marked his early career, just steady soldiering. The Mexican-American War came and went with him mostly on the sidelines, followed by stints at dusty outposts in Florida and Texas. Not glamorous, but it toughened him up, teaching him how to lead men in tough spots.

Fort Sumter: Caught in the War’s First Sparks

By 1861, the country was coming apart at the seams, and Doubleday was at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, when the Confederates let loose on April 12. Word is he gave the order for the Union’s first return a moment that kicked off the Civil War in earnest. The fort fell, but that split-second decision stuck his name in the history books, like it or not.

Gettysburg: A Moment of Grit, Then a Slap

Doubleday saw plenty of fighting, but Gettysburg in July 1863 was his crucible. When General John Reynolds got cut down, command of the I Corps landed in Doubleday’s lap. The odds were ugly, Confederates swarming, Union lines buckling. He scrambled, pulling together a defense that held just long enough for reinforcements to show up. Some say that the stand was the linchpin for the Union’s win at Gettysburg. But the next day, General George Meade swapped him out for John Newton. No explanation, just a gut punch. Doubleday never got over the slight, and it left a bitter mark on his record, even if he knew he’d done his part.

The Baseball Tale That Won’t Quit

Years later, a wild story popped up: Doubleday as the guy who cooked up baseball in Cooperstown back in 1839. It came from a 1907 commission pushed by Albert Spalding, a sporting goods tycoon with a knack for tall tales. Problem is, there’s no proof; none. Doubleday’s own writings don’t even hint at baseball. The game likely grew from old English and American stick-and-ball games, but the myth stuck like glue. Cooperstown got its Baseball Hall of Fame, and Doubleday’s name became a strange kind of shorthand for America’s pastime, true or not.

After the War: Quiet Years, Odd Turns

Doubleday didn’t hang up his boots after the war. He stayed in the Army, bouncing from Texas to San Francisco, where he got mixed up in setting up the city’s cable car system, random for a soldier, but there it is. He retired in 1873, settling into writing about military history and lending a hand to veterans’ groups. By the time he died in Mendham, New Jersey, in 1893, he was respected but never a household name, caught somewhere between a soldier’s life and a legend he didn’t ask for.

Historians have since shown that baseball evolved from older bat-and-ball games from both England and America. Despite the facts, Doubleday’s name remains welded to baseball in the public imagination.

The Real Doubleday

Abner Doubleday wasn’t a one-note figure. He fired the first shot at Sumter, held the line at Gettysburg, and somehow got roped into a baseball fairy tale. His career shows how history can twist a man’s life into something bigger or stranger than he ever intended. The myths might overshadow the truth, but his work as a soldier, grinding through the hard days, still deserves a nod. He was no saint or superstar, just a guy who showed up when it counted, even if the spotlight didn’t always follow.